Normandy: October 2024

- Anne Newman

- Dec 31, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 11, 2025

American Heroes

In these last hours of 2024, I have been thinking about my trip to Normandy in October. It seemed an apt place to visit. An unusually stressful U.S. election was pending, and I was worrying about the future of our republic. And how, as an American, I could draw strength from the past, when we helped save the world from tyranny. The simple act of remembering our heroes seemed a good place to start.

Our first goal was Honfleur, a charming and historic port town in Normandy which would be our base. The day after arriving, my husband Don and I set off for Omaha Beach on the English Channel.

Omaha was one of five beaches (Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha & Utah) chosen by the Allies in their long-planned and ultimately successful invasion of German-occupied France during World War II. This massive assault began on June 6, 1944, and involved thirteen countries including Britain, the United States, and Canada. On that day, D-Day, the Americans landed at Utah and Omaha. Omaha's geography and its German fortifications resulted in particularly heavy casualties.

There, in the sands, eighty years later, we saw a soaring memorial to the Allied soldiers, composed of three shining steel sculptures. I later learned that these wing-like forms were created by Anilore Banon and installed on June 5, 2004. Named Les Braves, the memorial honors the soldiers' bravery and sacrifice in that campaign, and reminds visitors what they were fighting for—'freedom', 'fraternity', and 'hope'. All needed now as much as ever.

Afterwards, we drove to the American cemetery which sits on the bluffs above Omaha. Row after row of white crosses, occasionally intermingled with white stars of David, mark the approximately ten thousand graves of those who died on D-Day and during the ensuing Normandy campaign. Walking among the graves of these Americans who made the ultimate sacrifice in a war against evil that so directly affected my European ancestors, I felt moved and grateful beyond words.

Family Stories

D-Day was the beginning of the end of World War II. But it would be too late to save my father's relatives in Czechoslovakia.

His maternal grandfather had died the year before in Theresienstadt, the German concentration camp near Prague. A maternal aunt, uncle and their families were still alive in that camp on D-Day, which must have given them hope if they knew about it. Yet within a few months they would be caught up in the last transports to Auschwitz and Dachau. None survived.

My father and his immediate family were luckier. In the summer of 1938, at age 18, his parents Rosa and Alfred sent him from their hometown of Brno, Czechoslovakia to London to continue his studies. When he arrived at Croydon airport outside London with his uncle Fred, he spoke only Czech and German. Fred, however, was a 'man of the world,' as the family called him, and spoke English. Ever resourceful, Fred had accompanied the Czechoslovak Legion as a translator across Siberia to Vladivostok during the First World War. Afterwards, he found his way back to Czechoslovakia via the Bering Straits, North America, and the North Atlantic. And now, after safely delivering my father to his new home with a family in Harlesden, North West London, Uncle Fred immediately returned to Prague.

My father's parents and his two sisters were able to follow my father to England in 1939, thanks to his older sister Olga. Her English in-laws had vouched for this Czech Jewish family who were offering employment to the British in the form of a glove factory, similar to the one Olga's husband and brother-in-law had owned in Prague. Bideford, a port town in Devon, was receptive, and so that is where the family lived during the war.

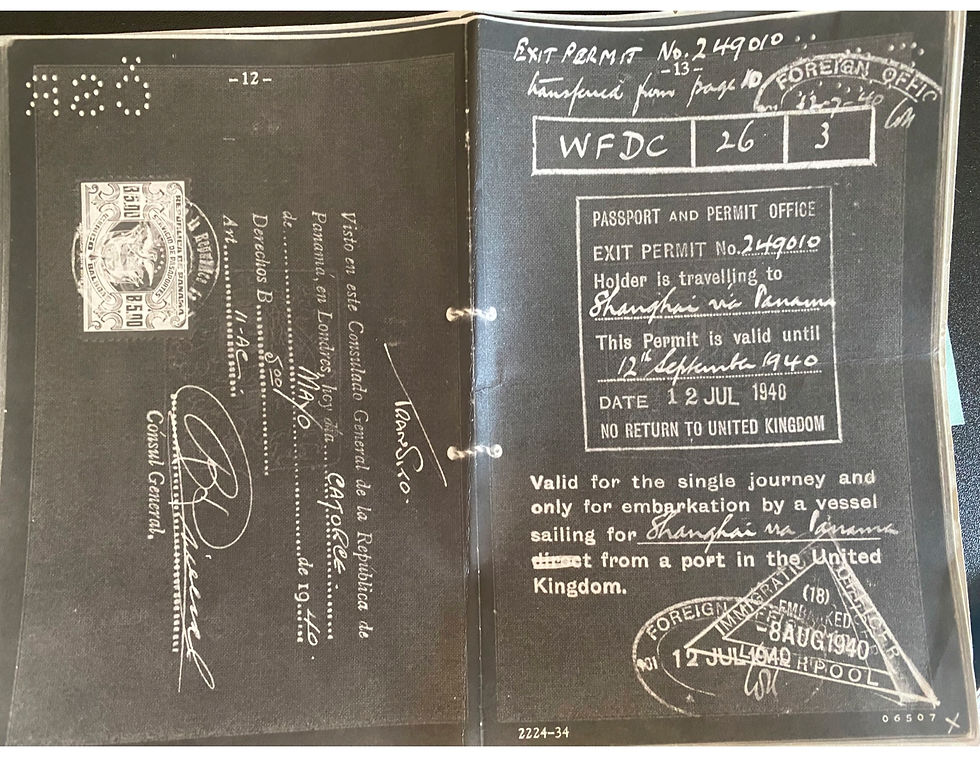

But by the summer of 1940, my father, age twenty, was preparing to leave. By then, he was fluent in English and a student at the Battersea Polytechnic Institute in London. With the Battle of Britain imminent, however, he and his parents were worried he would be drafted into the Czechoslovak Brigade. So they again looked to Uncle Fred for help. Fred had also managed to escape Czechoslovakia and had arrived in New York via Panama City in July. My father was encouraged to try to get to New York along a similarly circuitous route, which was necessary for Jews in those days. In his possession was a visa to Shanghai via the Panama Canal. The visa also stated "No Return to United Kingdom."

America

The day of my father's departure from Britain, August 8, 1940, was a tough one. "After saying goodbye to the whole family, which was not easy, I boarded the ship," my father wrote in his 1990 memoir. He was traveling alone. They left from Liverpool and sailed in a convoy of ships escorted by two destroyers. Most of the other passengers were Canadians, trying to get home. Fortunately, no U boats showed up; however, my father's problems were just beginning.

On arriving in Montreal, the first stop, he was surprised to be escorted off the ship by immigration officers. "They wanted to know why I was going to the Panama Canal. They suspected I {was} a German spy. They offered me a passage across Canada in a sealed train which for obvious reasons I did not accept. What did not help me was {my} Leica camera, which I am told, all good German spies had. I was also offered a trip back to England. That would have meant that I failed in my mission {to get to America} and I did not accept it either. Finally I was locked up in Montreal in what must have been their equivalent of Ellis Island..."

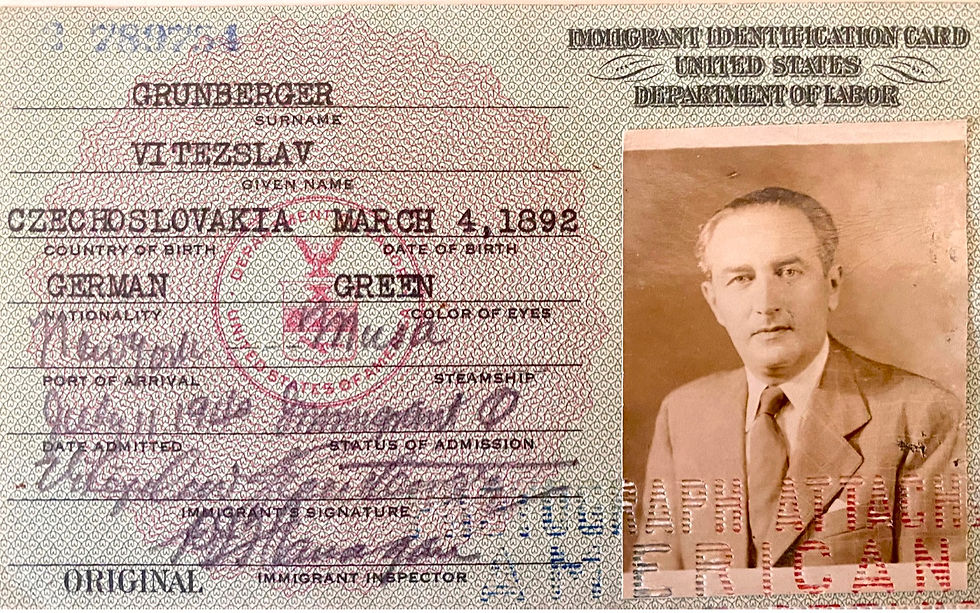

Uncle Fred, working from his new home base in New York, found an immigration lawyer for my father, and also encouraged him to interview in Montreal with a recruiter from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey. The interview went well, which my father attributed to wearing his "best attire": a double-breasted suit his mother had bought for him before the war.

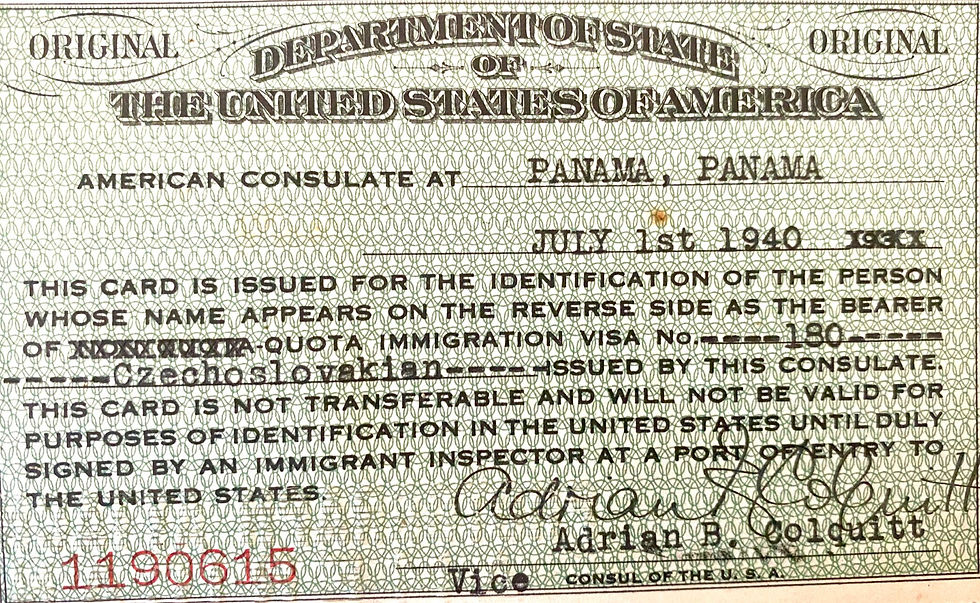

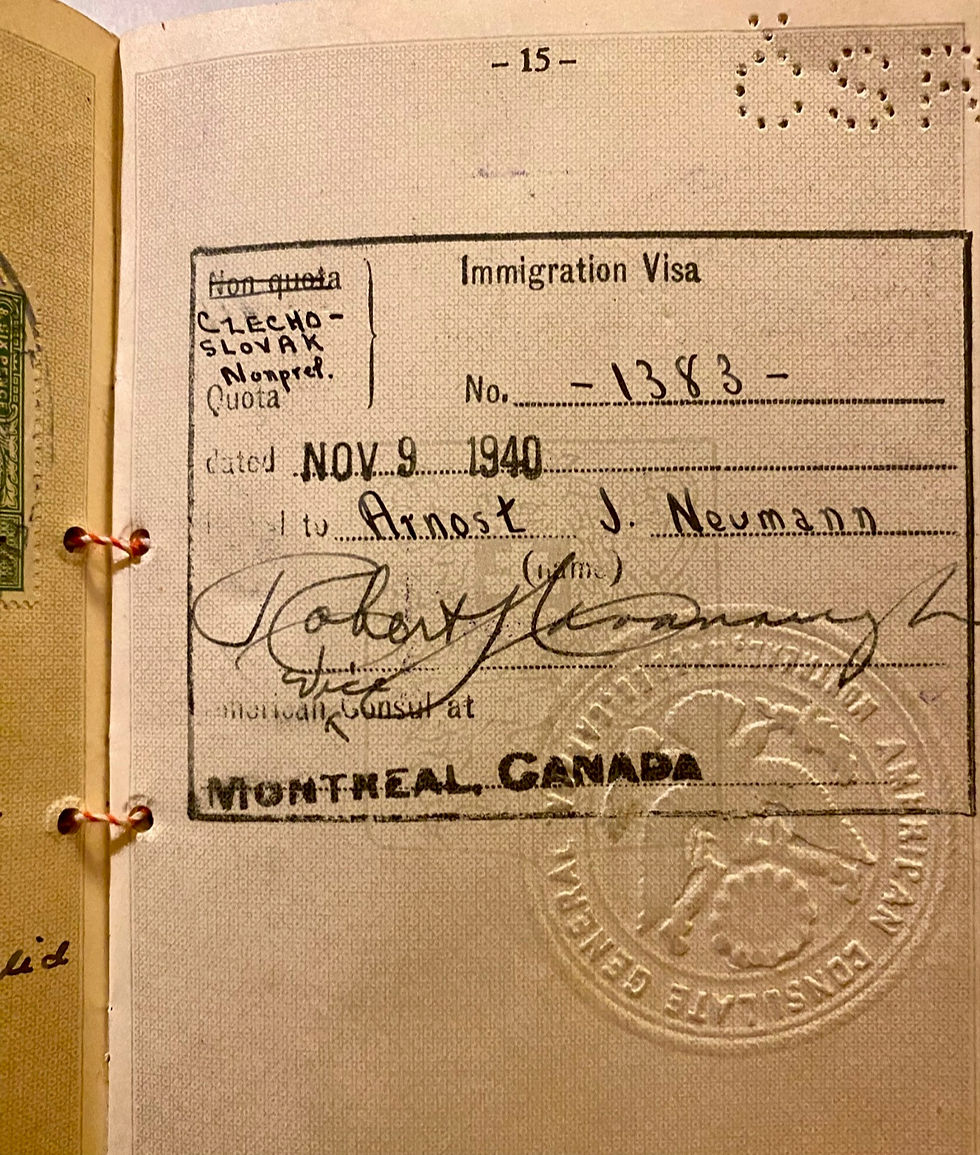

He had always resisted the clothes his mother chose for him. But in Montreal he was grateful for this suit, for he later learned its elegant tailoring had assured the interviewer he would be able to pay his tuition. He was admitted to Stevens with advanced standing as an undergraduate, and with his acceptance came a visa to enter the U.S. "I did not realize until later," he wrote in his memoir, "that the Czech quota {to the U.S.} was not filled, as Czechs could not leave the country to fill it." On November 9, 1940, three months after leaving England, he boarded a train for New York and was reunited with Uncle Fred. But in order to leave Canada he had to sign a paper that he would never enter that country again.

He was now persona non grata in Canada as well as the UK. Entrance and exit visas were extremely difficult to obtain during World War II, especially for Jews.

Becoming American

In June 1944, the Allies launched the Normandy invasion. The Americans were playing a major role in the effort to defeat the Nazis in Europe and my father wanted to be part of it. By then he was twenty-four and an instructor at Stevens in mechanical engineering.

In September, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He was partially color-blind which would have disqualified him but passed the test by secretly memorizing the charts that American Optical had developed to detect this condition. Afraid to tell his parents he had enlisted, he sent a letter to his younger sister Ditta instead. "I wanted to say that I was doing my bit for the war... My letter was unfortunately opened by my mother as soon as she saw my handwriting."

Rosa was probably relieved to learn that her son's value to the Navy would be as an instructor state-side. During the next two years, he taught radar while stationed in Bainbridge, Maryland; Gulf Port, Mississippi; and Navy Pier, Chicago.

In the meantime, Ditta served in the British military as an interpreter in the WAAF (Women's Auxiliary Air Force). Rosa participated in a weekly ladies knitting group in Bideford, where she knitted socks for seamen. And Alfred contributed to "Dig for Victory," by helping to grow vegetables in the garden as well as working for a small engineering company in Bideford when there was a shortage of personnel.

Shortly after being honorably discharged on June 14, 1946, my father sailed to England to see his parents and sisters for the first time since the day he said goodbye to them on the ship dock in Liverpool in 1940. He had become an American citizen in Chicago the previous January and was now welcomed everywhere.

On the boat on his way home, he would meet his future father-in-law, who had escaped Europe in 1941 with his wife and two teenage children, including my mother. Two years after being introduced in New York in 1946, my parents married and made their first home in Hoboken. A few years after that, I was born in a hospital in Manhattan and also began life as an American. A lucky and happy circumstance for my parents and for me.

Reflections

I did not think about all these tangents of family history while we were in Normandy. I just knew that our visit to that sacred place felt personal. Some of my ancestors died in the war that these American soldiers helped win, and others had opportunities and resources enough to survive and become Americans themselves. And I am one of the beneficiaries.

Perhaps one small way I can meet the challenges of my time is to keep the memory alive of those who lived that history. For it feels now like our turn. Freedom, fraternity, and hope are on the line again.

Places of Remembrance

Unlike the heroes we honor in Normandy, my father's relatives, like millions of others who were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators, have no graves. However, they are commemorated by name with the more than 77,000 other Czech Jews who perished in the Holocaust—the defining horror of World War II—in the Pinkas synagogue in Prague.

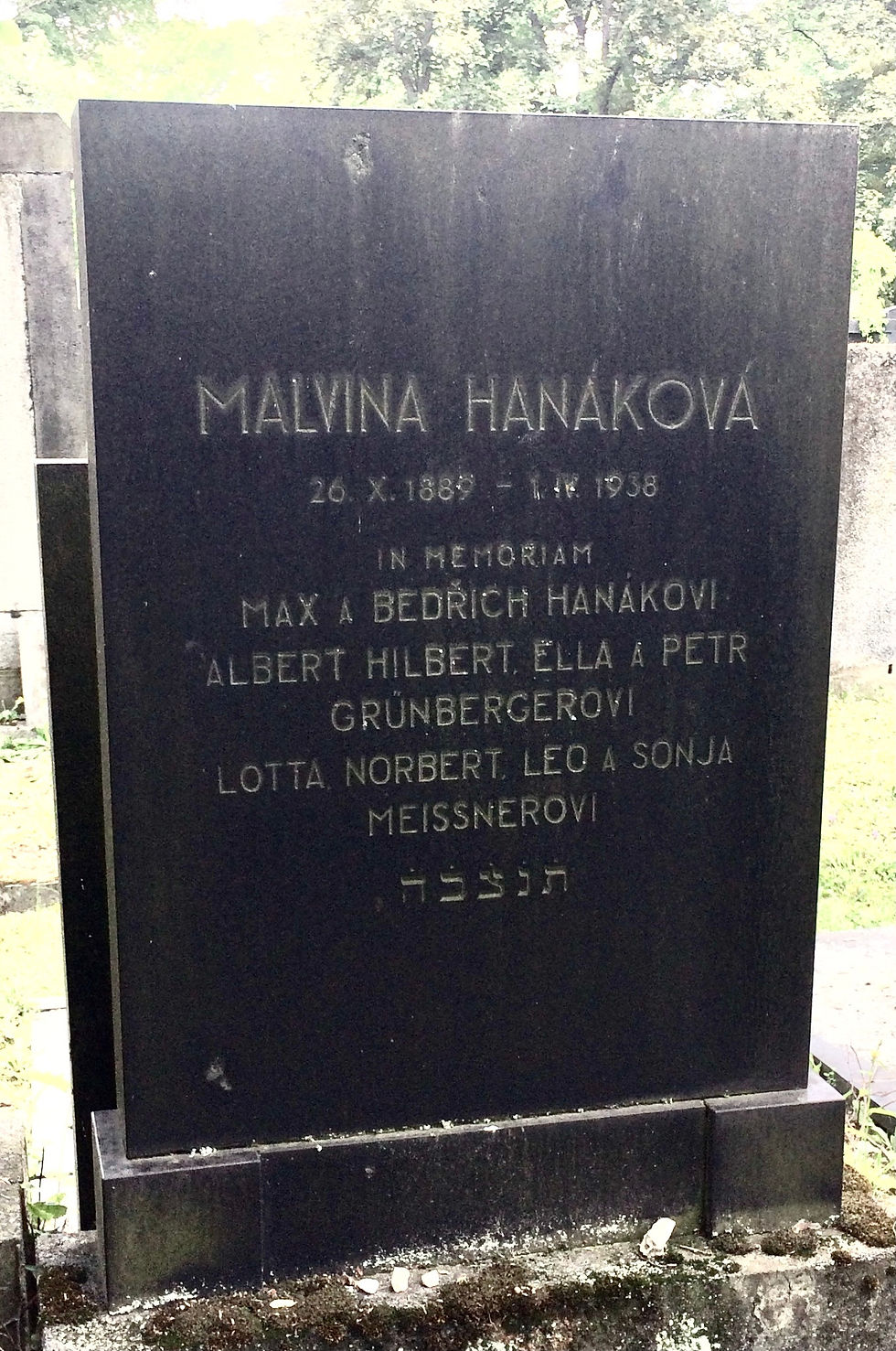

Some years ago, during one of my annual trips to Brno, I discovered another place of remembrance—the grave of my grandmother's sister Malvina Hanáková, who died in Brno in 1938 before the war. As I approached the headstone, one of thousands in the large leafy Jewish cemetery, I noticed that the tall rectangular marker also listed, in loving memory, the ten family members from my father's childhood who were lost during the war: his grandfather Albert, uncle Hilbert, aunt Ella, cousin Petr, aunt Lotta, uncle Norbert, cousin Leo, and Leo's wife Sonja, as well as Malvina's husband Max and son Bedřich.

Rosa and Alfred must have created this hidden memorial when they returned to Brno in 1946. Due to Rosa's failing health and the Communist takeover, their stay in Brno would be temporary. And when they left for good in 1948, no relatives would return for decades. Seventy years later, I was undoubtedly the first in my family to witness this personal reminder to future generations of what can happen when hate is allowed to flourish, and it took my breath away.

And a few years after that, I had the opportunity to offer my own remembrance: the laying of Czech memorial stones in front of the last homes in Brno and Třešť where these relatives lived before being deported. The bronze plaques, inspired by the German Stolpersteine, are called Kameny zmizelých, i.e., 'stones of the disappeared.' Each time I travel to the Czech Republic, I visit them with a cloth to clean off the dirt and make them shine again.

Newman, E.G. (1990). Unpublished memoir.

Comments